The Butterfly Effect

I. One summer, when I was in fourth grade, my family had an inflatable pool in the middle of our patio, the only flat space uninterrupted by the hill. The cheap pool’s tacky blue color and fake water-print were a forever staple of my childhood, and it seemed to attract insects of all sorts. We had many unique visitors, but my brothers were partial to the praying mantis who liked to frequent the side of the pool closest to the shade, far from the sun. We watched the mantis grow and change color and watched as its own eyes followed us around as ours followed it. But I preferred the butterfly.

I only ever saw it once. It was the life I saw for what it was.

It was the largest butterfly I had ever seen, dappled with sunshine and sharp black outlines that reminded me of the splattered paint in my art classroom. It intrigued me like nothing else, and became my immediate sole focus. This was the type of butterfly I only ever saw in the kid’s National Geographic magazines. I adored it for the fluttering seconds I observed it. I’d never seen nature so colorful before—my northeast region consisted of cold mud and excessive amounts of deer, finches, and various unknown roadkill.

But I knew everything about deer and death when I was ten.

They were predictable—but this life had the same core responses as I did, which felt new to me. It was fragile. It was lovely. To see such a beautiful creature that could very well have been an angel in disguise—at least in my mind—seized my childish brain and never ceased. A girl too young to have butterflies in her stomach yearned to at least feel them in her hands. Two beings so young, fleeting, delicate, and connected through the nervous twitches of new wings and the warmth of the sun. The butterfly was barely alive and in a way, I was too.

It was floating on the water’s surface when I peered out the kitchen window. Turning to my mom as she walked through the kitchen I asked her to look in the pool. She said it was a leaf and I said nothing. Unlocking the backyard door took only a minute, and I soon stood and stared at the floating crumple of fading life on the surface of the water, and then realized I was clutching the heavy skimmer with both of my unsteady yet determined hands. I almost toppled into the water on uncertain toes, but I hauled the skimmer into the water. The butterfly was fished out and poured onto the shady stone of the patio and I sat next to it for a while. I was beyond stressed—as much as a child could figure out anyway—what if it didn’t live and my hesitation killed it? Did I waste too much time and was it already too late by the time I saw it? Or was it my mother’s fault for not seeing it as something alive, worthy of saving, but would she feel as guilty as me? What does this make me? What will I do if it doesn’t get up—will I just leave it there or put it in a bush?

II. “How did we become friends?”

“We sat next to each other in class.”

III. Time was always a difficult fact for me to hold onto. It slipped through my fingers like rays of fading sunsets and flew through my head like forgotten flashbacks. I think that everyone can be confused by time. Sometimes it doesn’t feel like the appropriate amount passed or too much passed too soon. I have to set alarms within the hours of my day just to remind myself how much time has passed, usually in hour to half-hour increments of my phone going off for no other reason than to go off.

Time is moving through me, not with me.

IV. I read a lot about the “childhood friends “ trope and it always fills me with envy. Maybe that’s why I don’t like the trope as much as others. It’s not because I didn’t have childhood friends, I did. We just failed the test of time. We are now strangers who know each other’s houses as well as our own, who can fondly remember names of stuffed animals that aren’t ours, who know where every pot and pan and plate goes in a kitchen that isn’t ours, whose pets that aren’t our own can smell us and still think “family.”

Which is really unfortunate, because I think that we could’ve stayed friends. Maybe if I didn’t like fantasy books so much at the time. Maybe if I decided to keep playing soccer. Maybe if I picked up a basketball instead of a colored pencil. Maybe if I didn’t cut my hair. Maybe if I liked more boys. Maybe if I liked how my body looked in leggings. Maybe if I played with dolls. Maybe if I had sisters instead of brothers. Maybe if I lived in a different area. Maybe if I lived in their world. Maybe.

V. Back to the Future is a staple movie in my household. If you haven’t seen it, the name itself could hint at what it’s about. Time-travel. It basically set the foundational groundwork for “the rules of time-travel” from 1985 to the current day, but the rules are expectantly confusing, although, like time, coherent enough for the imagination to work through. The Butterfly Effect was the only thing I took from that movie. My brothers liked the model of the car and would try to figure out how time-travel could be possible in real life, but I just got scared. What if I made the wrong decision in my current timeline? It’s the only timeline I have.

VI. There’s no going back and fixing my mistakes.

VII. There’s no time like the present.

The butterfly didn’t actually die. It fluttered on and away, in time.

Author

Kaitlin Jeuch

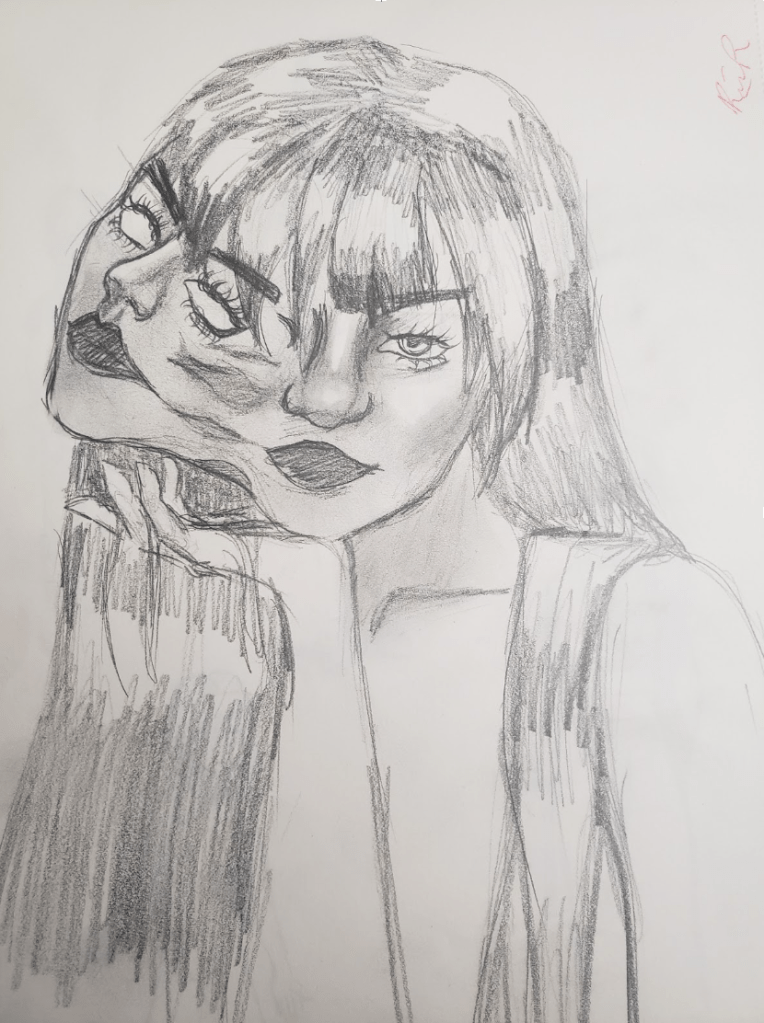

Artist: Ruhshona Rahmatova – “Black”